Ok, I haven’t written anything for this blog in a while and I know that there are other “n” topics out there. But I was having a conversation about illustrators vs. fine artists today and NC Wyeth came to mind—the penultimate illustrator who’s work hangs as example of classic American art. “[NC Wyeth]: one of America's foremost illustrators and painters.” (http://www.ncwyeth.org/)

Ok, I haven’t written anything for this blog in a while and I know that there are other “n” topics out there. But I was having a conversation about illustrators vs. fine artists today and NC Wyeth came to mind—the penultimate illustrator who’s work hangs as example of classic American art. “[NC Wyeth]: one of America's foremost illustrators and painters.” (http://www.ncwyeth.org/)Newell Convers Wyeth was born on October 22, 1882, in Needham, Massachusetts. Growing up on a farm, he developed a deep love of nature. His mother, the daughter of Swiss immigrants, encouraged his early artistic inclinations in the face of opposition from his father, a descendant of the first Wyeth to arrive in the New World in the mid-17th century. His father encouraged a more practical use of his talents, and young Convers attended Mechanic Arts High School in Boston through May 1899, concentrating on drafting. With his mother's support he transferred to Massachusetts Normal Art School and there instructor Richard Andrew urged him toward illustration.(www.ncwyeth.0rg)

In 1902, NC moved to Wilmington, Delaware and studied under Howard Pyle. Pyle is a legendary illustrator and was an influential teacher to an eager NC.

The master emphasized the use of dramatic effects in painting and the importance of sound, personal knowledge of one's subject, teachings Wyeth quickly assimilated and employed throughout his career. The astute young man recognized the value of Pyle's instruction, writing to his mother just after his arrival, "the composition lecture...opened my eyes more than any talk I ever heard." (BJW, p. 21) In less than five months, Wyeth successfully submitted a cover illustration to the Saturday Evening Post. (www.ncwyeth.org)

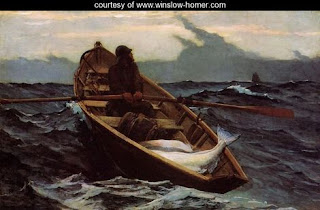

I have been fortunate enough to see his work in two museums, The Brandywine River Museum and the Delaware Art Museum. The light and drama Pyle helped him discover bowl you over when you encounter his work. Growing up, I knew his work as my ignition of imagination in Treasure Island, Ivanhoe, Robinson Crusoe, and The Last of the Mohicans. His bold characters, vibrant settings, and amazing story telling ability created the metaphor that many boys associate with swashbuckling pirates and seafarers of the tall ships. My mental model of his work usually includes dramatic settings and billowing clouds; wild lighting and fanciful coloring; and strong figures interacting in scenes which allow your imagination to put them in action.

In Last of the Mohicans, he employs a point of view that allows canoes to become fast-moving vehicles against the glass-like water and substantial rocks and mountains. He defines several fields of view and places his characters i n positions of significance interacting with each other and their surroundings. When I watched the chase scene in the modern movie interpretation, I couldn’t help but compare it to those paintings.

n positions of significance interacting with each other and their surroundings. When I watched the chase scene in the modern movie interpretation, I couldn’t help but compare it to those paintings.

n positions of significance interacting with each other and their surroundings. When I watched the chase scene in the modern movie interpretation, I couldn’t help but compare it to those paintings.

n positions of significance interacting with each other and their surroundings. When I watched the chase scene in the modern movie interpretation, I couldn’t help but compare it to those paintings.The first time I met my father-in-law, he took me to the Brandywine River Museum. My mother-in-law studied at the Barnes Foundation and he knew this would be a great outing for us to get to know each other. It stood for the full time of our lives together as one of my favorite experiences. He was not an artist, but he knew great art. When I saw Wyeth’s work along with Pyle’s, I was amazed at the scale and depth. His characters almost walk off the wall in all of their terrifying and wonderful glory.

.jpg)